As I began to research the Massey Harris 21A, I found its history intertwined with that of the Harvest Brigade. As a youngster I was well aware of something called “going south”. My uncle “went South” each summer, young boys often talked about soon being old enough to “go south”. As I researched the harvest brigade I discovered that it was the organized beginning of “going South”.

Harvesting grain had long been a local affair. On the farms in our local Nebraska area it had been the practice for decades that each farmer bound and shocked his own grain and then joined with other farmers to follow the thresher from farm to farm to thresh the grain.

This practice prevailed even though combines that cut and threshed the grain in one operation had been around for many decades. According to Thomas Isern in “Custom Combining on the Great Plains” Moore and Hascall of Kalamazoo County, Michigan tested a machine they invented in the late 1830’s. Machines made after that design were used in the area until 1853. (But those who saw it work were content to use their binders and threshing machines.) One machine was shipped around Cape Horn to California in 1854. That machine burned to the ground in its third year in California. But local farmers had seen it work and began building their own versions. The most successful builder was the Holt family of Caterpillar fame.

Large fields, low humidity, and shortage of seasonal workers made the combine much more attractive to farmers in California than to those in the Midwest. While combines took over the vast majority of harvest in California and Oregon, only a few machines made their way back east. As early as 1901, a 16-foot combine was used west of Great Bend Kansas. Combines were also introduced in Saskatchewan and Montana, but acceptance was slow.

Higher grain prices in 1917 and 1918 caused some farmers to invest in combines. More were purchased over the next decades. But the binding and threshing system still prevailed.

World War II in Europe caused a great demand for wheat from the U.S.. There were still many young men willing to work for low wages so manpower was readily available. But once the U.S. joined the war that changed drastically. There was much concern that the large crops U.S. farmers were producing could not all be harvested. Mechanization of harvesting sounded like a great idea. But this was a time of rationing as well. There were limitations on how much steel, rubber, etc, manufacturers could purchase.

Joe Tucker was the man of the hour. He and fellow Massey Harris manager Tom Carroll had previously recognized a need in Argentina. Massey Harris was a major supplier of farm equipment in Argentina but did not have a combine in the line-up. They decided to build a combine- -not just any combine but one that was self-propelled. Up to that time (1938) the vast majority of combines worldwide were pull type. Early ones had been ground driven and pulled by horses – up to 36 to pull one machine. Once tractors became common, they were used to pull the machines. In most cases there was a separate engine on the combine to power the threshing mechanism.

Creative farmers in Argentina were taking these combines as a basic unit and adding a second engine to drive the wheels on the combine, making it self-propelled.

Tucker and Carroll took the hint and set out to market a Massey Harris self-propelled. The first machine was tested in 1938. The Model 20 worked well but was too heavy and too expensive to be commercially successful--about 900 were made. In 1941 they offered an improved machine called the Model 21.

So back to the problem of harvesting all that wheat in the U.S. Joe Tucker presented a report to the War Production Board (who controlled rationing in the U.S.) saying that if they would allocate steel, rubber etc that Massey Harris would build 500 machines that would be dedicated to the 1944 U.S. grain harvest. Each prospective purchaser would have to commit to harvesting 2000 acres with each machine. In order to harvest that many acres the combines would have to start harvesting in Texas in May and continue moving north all summer to end up in North Dakota, Montana or Canada. The War Production Board approved the plan.

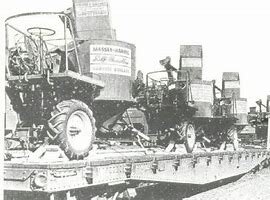

Some of the first combines were delivered by train to Corpus Christi, Texas, where the new owners could take delivery. Other delivery points were Enid, Oklahoma, Altus, Oklahoma and Hutchison, Kansas.

By this time Massey Harris had begun making the model 21A. It differed from the 21 most noticeably in that it utilized an auger header as opposed to the canvas headers common at the time. From the references and pictures I have seen my conclusion is that the 500 machines of the Brigade were a mixture of 21s and 21As.

Tucker did a superb job of publicizing the undertaking. He sent notices to newspapers and awarded prizes for most grain cut. County Extension Agents were active in pairing cutters with farmers in need. Truckloads of parts followed the Brigade across the country. Airplanes were used to scout ahead to check on the ripening process.

The Brigade was successful in meeting goals set for acres and bushels cut. It was extremely successful in making Massey Harris the foremost brand of self-propelled combine.

Train load of combines. Pick up points included Corpus Christi, Texas, Enid, Oklahoma, Altus, Oklahoma and Hutchinson, Kansas.

Bobbie Smith buys His first combine.

One of those taking part in the 1944 harvest adventure was 21-year old Bobbie Smith of Arnold Nebraska. He bought a new truck, new pickup and a 21A Massey Harris combine for $4700 ($3200 for the combine). His first stop was at Crowell, TX. The next stop was Hobart Oklahoma, then Medicine Lodge and Plainville in Kansas, then on home to Arnold. From there it was on to Williston North Dakota and a couple of times to Circle Montana.

Bobbie remembers that the farmers were hesitant to allow the new machines in their fields. The main question was, “Will it save the grain?” They must have been convinced because he was very welcome the next year.

The obvious advantage of the self-propelled over the commonly used pull-type was “opening the fields”. One of the jobs Bobbie got was only to open the fields.

He got one job (a section of wheat) on the condition that he would buy the farmers pull type combine. He sent for his brother and a tractor from Arnold. They used the pull-type and the self propelled on a number of jobs before selling the pull-type in the Arnold area.

For the main part the 21As were equipped with an electric motor to power the header lift. There were three springs under the combine to counter the weight of the header. Bobbie remembers the constant need to adjust the tension on those springs. If the motor had to do to much lifting it would run the battery down. If the spring was too tight the header would bounce up and the farmers would be displeased with the cutting height.

Bobbie’s first machine did not have a lift motor. Instead it had a hand wheel. Bobbie’s younger brother Max recalls that as a young teenager he was not able to manage the hand wheel so he got the job of operating the pull-type machine.

Bobbie has always been a proponent of clean sharp looking equipment. He recalls cleaning up his machine in Medicine Lodge before moving on to Plainville. At Plainville he got work ahead of machines there that had not been cleaned up.

He paid his hired men $300 a month plus room and board. His first job at Crowel paid $2.50 per acre but everything later was $3 per acre. The hauling charge was 5 cents per bushel.

Loading the combines was a big job. The sideboards of the truck had to be removed and a railing attached to each side. Extensions had to be installed on the header lift to give extra clearance over the cab. Then the correct bank had to be found to allow the drive wheels to go on the truck bed. The truck had to be driven forward to allow the back wheels to drop so the header would clear the cab. (Bobbie says that in six years he was never able to get a truck into Kansas without a ding in the cab due to the rough road north of McCook.)

Bobbie says they roaded the machine one time. That was from Crowell to Medicine Lodge, about 108 miles using today’s roads. Reversing a couple of pulleys on the drive train enabled the 21A to travel up to 7 miles per hour. That would mean about 15 hours on the road.

1950 Wheat Harvest

The big wheat harvest around Arnold was nearing a close this week as the bulk of the bigger fields have been harvested.

Pictured above is a field being being harvested on the Smith farm on Garfield Table last Thursday when six self-propelled combines were cutting this wheat at one time.

The combine operators were Max Smith and Ralph Nansel of Arnold and Victor Beham, Don Mcoy, Alvin Krenek and Wes Hardin of Caldwell, Kansas. The combine operated by Max Smith was a 16-footer and the other five were 14-footers. When all six combines went down the field together, they were cutting a swath of wheat 86 feet wide.

The wheat yield has been exceptionally good this year. Bob Smith reported that the field this crew had left that morning made around 36 bushels to the acre and the field they were cutting when the picture was taken, was making around 30 bushels.

A concern was given to dampness of the wheat straw, up to three bushels per acre were lost because the combines couldn’t chop the straw up fine enough.

This field was typical of many fields around Arnold, with reports of from 25 to 35 bushels being made. There were reports of small patches of summer fallow wheat making over the 40 bushel mark in some areas.

Photo and text from The Arnold Sentinal.